Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate FAQs

By David Fisher, MD, Levine Children’s Hospital

By David Fisher, MD, Levine Children’s Hospital

Cleft lip and palate remain one of the most common birth defects, affecting up to one in 700 live births. I meet with parents during pregnancy and newborns with cleft lip and palate all the time. One of the most important things to explain and show with pictures and individual stories is that the diagnosis of cleft lip and palate does not have to define the children or families. We have excellent treatments and a great team of specialists who work together on all aspects of care.

What is a cleft lip and palate?

A cleft lip occurs when the normal process of the joining of the lip does not occur. Sometimes this can be linked to a specific genetic change, but most of the time this occurs spontaneously for no known reason. Sometimes there is just a small “notch” in the lip, and sometimes the cleft carries through the full height of the lip into the nose. The lip is usually seen on ultrasound during pregnancy. If there is a cleft, it is often picked up by your obstetrician.

The palate forms the roof of the mouth and is “hard” in the front (formed by some of the bones of the mid-face) and “soft” in the back (formed by muscles that help with speech and swallowing). A cleft palate occurs when the two halves of the palate do not join properly during pregnancy. It may occur along with a cleft lip, as an isolated cleft palate, or with another difference in development.

What is the soft palate?

The soft palate is the back part of the palate that contains important muscles to help with speech and swallowing. Normally the soft palate moves toward the back of the nasal passage and helps form certain sounds. When there is a cleft of the soft palate, these muscles do not connect, and the normal movement of the palate is disrupted. Children have difficulty making certain sounds (e.g. b, d, k).

What is the hard palate?

The hard palate forms the front part of the palate containing bone that supports the upper teeth and the midface. This separates the mouth from the nose and also helps with feeding and the formation of certain sounds (e.g. d, s, t).

How is a cleft lip and palate diagnosed?

A cleft lip can usually be seen on ultrasound during pregnancy, and when there is a cleft palate it may sometimes be seen. When a palate occurs on its own, it is usually seen when your child is born. Often times one of our pediatric genetics doctors will also evaluate your child after birth.

How does a cleft lip and palate impact speech?

One of the most important functions of the palate lies in the development of speech as children grow. There are physical factors (the anatomy of the palate and nerve function of the muscles) as well as cognitive factors (the brain’s ability to learn language) that work together to help children learn how to talk. The speech and language therapist plays a critical role in helping children and families develop normal speech. The plastic surgeon helps to restore normal anatomy of both the soft and hard palate.

When is a cleft palate treated?

A cleft lip is usually closed by six months of age. A cleft palate is usually closed by 18 months of age before the child begins to develop the core sounds for speech.

What does this mean for my child?

Most children can and will achieve normal speech. Some children may require additional surgery on the jaws or palate as they grow. Your cleft surgeon will follow your child to ensure they are developing normally and will coordinate care as a team with other specialists as indicated.

David Fisher, MD, is a plastic surgery specialist in Charlotte, North Carolina and practices at Levine Children’s Hospital. Dr. Fisher delivers advanced, compassionate care for children with complex conditions affecting the head and neck and performs major reconstructive procedures to correct abnormalities and improve children’s health.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Supporting Children with Spasticity

By Sarah Jernigan, MD, MPH, Carolina Neurosurgery & Spine Associates

When you hear the word “spasticity,” what do you think of? Many people think of the term “spastic” used for years to describe people with cerebral palsy (CP). This term was likely inspired by the sometimes jerking and seemingly uncontrolled muscle movements of those who manage CP. Sadly, it can be a colloquial term used to make fun of someone who is uncoordinated or incompetent, but for someone who lives with spasticity every day, the condition is no laughing matter.

When you hear the word “spasticity,” what do you think of? Many people think of the term “spastic” used for years to describe people with cerebral palsy (CP). This term was likely inspired by the sometimes jerking and seemingly uncontrolled muscle movements of those who manage CP. Sadly, it can be a colloquial term used to make fun of someone who is uncoordinated or incompetent, but for someone who lives with spasticity every day, the condition is no laughing matter.

Spasticity is a condition that can greatly impact a child’s ability to walk and perform other day-to-day activities, and it’s surprisingly common. Two out of every 1,000 children in the United States are born with CP, and 75 percent of those children have spasticity. It can also impact children who have multiple sclerosis or have experienced traumatic brain injury, stroke or spinal cord trauma.

People who live with spasticity describe spasticity as a range of feelings, from a mild sensation of tightness to severe, painful spasms. To understand what spasticity looks like, think of a child living with CP who is sitting with her legs crossed. Her leg might suddenly kick out or jerk forward. This child might be perfectly aware the kick is going to happen, but she may not have the muscle control to prevent it or control her leg.

It’s important to note that spasticity is caused by a dysfunctional signal that loops between the brain, spinal cord and nerves in the arms and legs. Spasticity is not a sign of decreased intelligence or cognitive function.

Spasticity can greatly limit mobility and generate significant discomfort. Although many children (almost 50 percent) with cerebral palsy can walk with the assistance of braces, canes or walkers, spasticity can eventually rob them of that ability.

Spasticity can also negatively impact other parts of the body, including the tendons and ligaments. These changes can cause muscle stiffness, atrophy (deterioration or wasting of the muscle) and fibrosis (changes in the properties of the muscle fibers). Muscles affected by spasticity have difficulty stretching the proper length needed to keep up with a child’s bone growth. The muscle then becomes shorter than it should be and prevents a joint from achieving normal, full range of movement. This condition is known a contracture, and can lead to significant pain and bone deformities.

So what can we do to help children living with spasticity to live their best life?

The initial evaluation for spasticity includes a comprehensive assessment of the presence, severity and impact of spasticity on the child. Physical and occupational therapists evaluate which muscles are affected and start by stretching these muscles. A physiatrist may also prescribe muscle relaxants to help block the abnormal nervous system signals. If these treatments are not effective, Botox injections into specific muscle groups may also help loosen these muscles and stop the cycle of spasticity.

Surgery may be an option in children with more severe spasticity or for patients who do not respond to these other treatments. Two surgical treatment options for spasticity include implantation of an intrathecal baclofen pump and selective dorsal rhizotomy.

Baclofen is a medication used with spasticity treatment. It is a central nervous system depressant and skeletal muscle relaxant. A pump can be implanted into the spinal fluid space and provide baclofen directly to areas of the spinal cord where it is most needed to loosen muscles and prevent spasms. This is appealing because the pump can be removed leaving no lasting or permanent effects.

Selective dorsal rhizotomy is a surgical procedure in which a neurosurgeon permanently cuts the nerves that are firing abnormally and contributing to spasticity. Those nerves are then partially or completely cut, to stop the dysfunctional signal loop, and decrease the spasticity. While the results of this surgery are permanent, these patients must continue with additional spasticity therapies throughout their lifetime.

Taking care of children with cerebral palsy and spasticity requires a team approach from families, therapists, physicians and you. Taking the time to understand spasticity is a great way to be a supportive friend, classmate or neighbor, and can help everyone reach their maximum potential.

Sarah Jernigan, MD, MPH, is a fellowship-trained pediatric neurosurgeon with Carolina Neurosurgery & Spine Associates, home to the largest team of pediatric neurosurgeons in the Southeast. Dr. Jernigan specializes in diagnosing and treating children with brain tumors, hydrocephalus, spasticity, craniosynostosis, spina bifida and vascular disorders such as Moyamoya disease.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

How To Talk with Your Children About Difficult Topics

By Frank Gaskill, PhD, SouthEast Psych

We live in very strange times. As adults, our brains are not wired to process the world in which we currently live. It’s easy to forget what life was like before the internet, the 24-hour news cycle and social media. But this summer I remembered. Social media and most news was gone from my life for seven weeks. The first days were rough because being on my phone was such a habit, but then I just forgot. I found I could concentrate better, had more ideas and communicated more with my family. I was also significantly less stressed.

Now imagine being a child in this world.

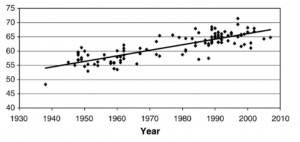

Their world is an incredibly stressful and unpredictable place filled with terrorism, scary weather patterns and political strife. At the same time, kids are now more depressed and anxious than at any other time in history. Sadly, suicide is also on the rise. Some longitudinal research suggests that kids today have levels of anxiety comparable to children hospitalized for anxiety in 1957. In another 2010 study from Clinical Psychology Review, the significant increase in depression is graphically documented.

In addition to all this stress and depression, social media tells kids they should be happy, popular, and semi-famous either through YouTube or Instagram. And the gap between social media’s message, “Be Happy!” and the message from the news, “Be Scared!” is widening.

And this is why parenting right now is so important. And by parenting, I mean talking about difficult topics. Talking with a trusted adult actually reduces stress, anxiety and depression.

So Where Do You Start?

What’s a difficult topic? I include sex, drugs, terrorism, suicide, kidnappings, divorce and death just to name a few. While this is a crazy variety of subjects, the underlying theme is these are the topics that usually make parents squirm. But wouldn’t you rather your kids discuss such things with you than someone else?

Here are five guidelines I often suggest for parents to consider:

- Difficult topics are ongoing conversations. It’s not just one talk. And before diving in, check your relationship first. While you may want to talk with them, they may not be willing to listen to you, especially teens. Entering into these conversations requires trust and openness.

- Before you talk, think through the emotional and developmental maturity of your child. Some 9-year-olds can handle topics for which some 12-year-olds are not prepared. All kids are different. And, kids are detectives. All their answers can be found online. Online information may be misleading, developmentally inappropriate, or just not compatible with your family’s values. It’s better for them to learn from you.

- With many topics, you as a parent will feel uncomfortable as well. Acknowledge your emotions to yourself and to your child. Recognize they likely are feeling similar and it is comforting for them to know you understand and are experiencing similar emotions.

- Before a conversation, practice by yourself or talk it through with a friend or partner. You never know what emotions may well up in you especially around loss, sickness, or family strife. It’s ok for you to show your emotions, but don’t overwhelm your child or put them in a position of trying to comfort you.

- Reassure them. Let them know they are loved and protected. Show them leadership, and be their safe space. These conversations don’t need to be long and preferably, should be brief. Some kids may take time to process the information. Be sure to ask them specifically if they have questions. Reassure them that they can come to you at any time for more information. It never hurts to check in with them later.

Making a habit of being able to talk about difficult topics makes you a better parent, relieves guilt and builds confidence in your child. Also, demonstrating your willingness to have these conversations also conveys love and demonstrates confidence in your child’s ability to engage with you. And finally, for the long-term, your child is seeing you model a level of parenting that they, too, will hopefully model with your grandchildren.

“Dr. G” specializes in Aspergers and the Autism Spectrum. Dr. G works with children and adolescents using a family based approach. He also serves as a member of the private schools admissions testing team (CAIS). Dr. Gaskill is the author of the graphic novel Max Gamer, a contributing author to The Walking Dead Psychology, and Star Wars Psychology: The Dark Side of the Mind. He is also the host of the Dr. G. Aspie show (“Asperger’s is Awesome!”).”

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Pediatric Surgery: A Wife’s Perspective

By Alison Schulman

In March 2017, Dr. Andrew Schulman wrote a popular blog post titled “A Day in the Life of a Pediatric Surgeon,” which described a busy, sometimes chaotic 24-hour period during which he balanced being a doctor, colleague, husband and father. We asked Dr. Schulman’s wife about the other side of this demanding schedule. Here’s what Alison Schulman had to say.

How did you and Andrew meet?

We were both at the University of Virginia doing our medical residencies in surgery. I met Andrew when I was at the end of the first year of my residency; he was finishing his fourth. When it became apparent we were going to be together long-term, I decided to stop my studies in medicine. There is not a day that I regret my decision. I love being available for my kids.

Andrew completed his subspecialty training for Pediatric Surgery at the Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center in Seattle. We jetted back to my hometown of Houston to get married and had a four-day honeymoon because Andrew had to get back to be on-call. Kate (now 11) was born 15 months later. When she was eight months old, we moved to Charlotte for Andrew’s position at Pediatric Surgical Associates. About two years later, Max (now 8) was born. We love it here in Charlotte. The people and practice continue to be a great fit.

What is the hardest thing about Andrew’s job?

I’d say the hardest part is thinking I know what his schedule is for the day – but never really knowing. At any second, he might get pulled away. This weekend, he wasn’t even on call, but he spent hours on the phone to ensure everyone at the hospital knew the necessary details about a complicated patient.

Having spent time inside surgery culture, I knew what I was getting into. But it definitely took me a couple of years to get used to it. Nowadays, I just don’t plan anything for weeknights, and we don’t go on vacations where Andrew will be unreachable. Especially with young children, I generally have to assume that Andrew is not going to be available. It’s a pain, but after a while you get used to it and when he’s here, it’s like a bonus!

It’s hardest on the kids, but they are old enough to understand how important his work is.

Is the work worth it?

There are two things about work that Andrew really enjoys. First is the actual operating, particularly when it’s something that will really change an outcome for a child who is extremely ill. He loves finding new ways to approach a problem and find a solution. Second is seeing the kids come back to the office in better health, particularly the ones who have had complex issues. For example, with some rectal surgeries, a surgeon will perform an operation on a newborn baby but not know if the surgery was successful until the child is toilet-trained. Andrew will come home and say how glad he is that a patient is able to poop on his own!

Despite the impact on our personal lives, our family knows Andrew is helping families in what can be their darkest hour. What help us with this understanding is knowing the other doctors in the practice have Andrew’s back, and that he has theirs. This is a rare situation in healthcare. At PSA, you never feel like someone is working more than someone else. It’s truly a group effort.

The surgeons at PSA are all family first, and the practice is part of the family. The other doctors’ wives and families all support each other. We make sure every doctor gets to important functions for his family, because we all get it. We make it work, and it works for us. PSA is a true team.

What is it like to have Andrew home?

Obviously, Andrew’s time off is incredibly valuable. When he’s home, he tries to do normal “Dad” things, like pick up the kids from school. I know many dads do the morning drop-off, but by that time, Andrew has usually been at work for two hours or more. But when he’s off duty, he really loves getting to do those little things with our kids – that, and barbecuing!

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Comforting Kids Before Surgery

By Andrew Schulman, MD, and Megan Tillery, RN Supervisor

Whether your child is scheduled for a simple procedure, like getting ear tubes, or preparing for major surgery, many of the questions we receive from our young patients (and their parents) are very similar. As medical professionals, it’s important for us to be as open, honest and clear as possible. As pediatric surgeons and nurses, it’s important for us to help moms and dads communicate expectations accurately, with the right amount of reassurance.

Whether your child is scheduled for a simple procedure, like getting ear tubes, or preparing for major surgery, many of the questions we receive from our young patients (and their parents) are very similar. As medical professionals, it’s important for us to be as open, honest and clear as possible. As pediatric surgeons and nurses, it’s important for us to help moms and dads communicate expectations accurately, with the right amount of reassurance.

Will it hurt?

This is the most common question that patients ask. First, we tell children that they will feel nothing at all during surgery. Afterwards, they maybe sore, but that soreness can be managed with over-the- counter medication or a prescription, if needed.

Will I be awake during the surgery?

If the child is very young, we explain to him/her that we will give them a special type of medicine to help them fall asleep. We reassure the child that he/she will not feel or remember anything from surgery. Occasionally doctors will perform minor procedures in the office where the child would be awake, but for the most part, he or she will be under anesthesia.

Can my parent(s) be with me in surgery?

We tell children that their parent(s) can be with them until they go back to the operating room before the surgery, well after they have fallen asleep. Though no parents are allowed in the operating suite, we like to inform them that many of the doctors and nurses present are moms and dads, and that we promise to treat them with as much care and concern as we would our own children. We assure them that their parent(s) will be there with them when they wake up.

Can I have my blanket/stuffed animal?

Comfort items like blankets and stuffed animals cannot be part of a sterile procedure. However, we reassure patients that they can fall sleep with their favorite item. Afterwards, the nurse staff will make sure that it is kept in a nice, safe place during the procedure and returned to the patient before they wake up.

What, exactly, is going to happen when I am asleep?

Children are smart, and some really want more detail about what is going to happen and why surgery is necessary. It’s important to give enough information to answer their questions, but not so much to cause panic. For major surgeries, we work with parents closely on this question, and we offer these guidelines based on the child’s age, or equivalent developmental ability to understand:

- Toddlers: We explain that we are going to do something that will fix their problem and make them feel better. We might describe the problem using analogies or rough sketches for children who are a little older and want to know more.

- Preteens: We offer a little more detail on the problem and the solution. We also try to reassure them by sharing how many other kids their age experience similar procedures.

- Teens: For teenagers, we typically give them as much detail as they want, and provide them with age-appropriate resources should they want to know more. At this age, it’s important for them to understand what is going to happen so that we can obtain their approval for surgery. Parents give consent to those under 18.

When can I go back to sports/swimming/physical activity?

This varies depending upon the procedure, but generally we instruct children to wait two weeks before returning to sports, swimming or strenuous physical activities. In “kid time,” two weeks sounds like an eternity, so we remind them that recovery is a good time to watch shows, play games and catch up on movies.

Is this a really big deal?

There are times when the task at hand is complex and far from routine. During these times, children and parents can be understandably frightened and fearful of the surgery and outcome. Our communication philosophy remains the same – we strive to be open, honest, clear and reassuring.

The Charlotte region is lucky to have two exceptional hospital systems, along with some of the country’s best medical professionals. We hope that your child will never need surgery, but if they do, know that some of the nicest and most caring people you could ever met are there to help your family through this stressful time.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Is it Time for Ear Tubes?

By Christopher Tebbit, MD, Charlotte Eye Ear Nose & Throat

Your baby is fussy and seems to be in pain. It looks like they have an ear infection. Another one. Chronic ear infections can be a problem for many small children, but how do you know when it’s time for them to get ear tubes?

Your baby is fussy and seems to be in pain. It looks like they have an ear infection. Another one. Chronic ear infections can be a problem for many small children, but how do you know when it’s time for them to get ear tubes?

What causes ear infections?

The middle ear is an air-filled cavity separated from the outer ear canal by the paper-thin eardrum. The Eustachian tube is the passageway that connects the middle ear to the back of the nose. This passageway allows air pressure to equalize and prevent fluid from accumulating in the middle ear space. If the Eustachian tube is not working well, middle ear problems, including recurrent ear infections, can develop.

In children, the Eustachian tube is often dysfunctional due to its small size and swelling from respiratory infections. Without ventilation, a vacuum draws fluid into the middle ear space, creating a risk of infection or persistent fluid. Signs of ear infections can include ear pain, trouble hearing, fever, and ear drainage.

While middle ear infections cause pain and irritability, another concern is the impact they have on hearing. The fluid prevents the eardrum from moving appropriately, so sound does not get conducted to the inner ear. If a child has recurring ear infections, the constant blocking of sound can impact their speech development.

How are ear infections treated?

The best way to try and keep children from getting ear infections in the first place is to keep them away from sick children or other aggravating factors, like secondhand smoke. Yet despite the best hygiene efforts, many children will still suffer from ear infections. Additionally, if a child’s parents were prone to ear infections when they were young, their child has an increased chance of getting ear infections, too.

The standard treatment for ear infections is a course of oral antibiotics. However, if ear infections recur frequently, or if fluid persists in the middle ear, the doctor may suggest your child get ear tubes.

Ear tubes are soft, tiny cylinders placed through the eardrum that allow air into the middle ear. Short-term tubes are smaller and typically stay in place for six months to a year before falling out on their own. Long-term tubes are larger and secured in place for a longer period of time.

Ear tubes are a good solution for children with recurrent ear infections or persistent middle ear fluid that creates hearing loss. Tubes ventilate the middle ear space, bypassing the dysfunctional Eustachian tube.

Ear tubes benefit patients in several ways. First, they very often decrease or eliminate ear infections. If an infection does occur when tubes are in place, the infection can be treated with medicated ear drops, avoiding the need to use oral antibiotics. Restoring normal hearing by removing fluid from the middle ear space is another benefit of ear tube placement.

Ear tube surgery is very safe, with about 700,000 cases performed each year. The procedure takes about 10-15 minutes, with the child briefly asleep under light anesthesia.

Dr. Tebbit is an otolaryngologist who specializes in comprehensive adult and pediatric ENT care. He practices in CEENTA’s Belmont office. CEENTA doctors have been involved with ear tube surgery since the very beginning, as ear tubes were actually invented by CEENTA’s own Beverly Armstrong, MD, in 1952.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

How to Help Prevent Eating Disorders

By Juliet Lam Kuehnle, MS, NCC, LPC, and Heidi Limbrunner, PsyD, ABPP

By Juliet Lam Kuehnle, MS, NCC, LPC, and Heidi Limbrunner, PsyD, ABPP

We’ve all heard our friends make comments about what they “shouldn’t” have eaten that night out at the restaurant. Or perhaps you yourself have commented about needing to get to the gym to makeup for a meal or to achieve the goal you’ve set for yourself in response to a diet or exercise trend. Maybe you’re familiar with the self-talk you experience when looking in the mirror or comparing yourself to the person standing next to you. You may think these are simply inward thoughts that only impact your self-esteem, but that is not the case.

The reality is that our children, at younger and younger ages, now often have this same body awareness and have already started to buy into these societal messages of the “thin ideal.”

Eating disorders are mental illnesses that affect women AND men and girls and boys of all ages. They have the highest mortality rate of any other mental illness and include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, ARFID (Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder) and binge eating disorder. Our society’s cavalier attitude toward weight, size and shape, combined with a lack of understanding about mental illness, contribute to the widely-held misconception that eating disorders are a choice or rooted in vanity. While it can begin as an attempt to lose weight, for example, these disorders are truly about managing discomfort and emotional stressors.

The most common question that we get from parents is what caused their child’s eating disorder. While it is impossible to pinpoint the exact cause, we know that it is a culmination of several biological, psychological and sociocultural factors. It is estimated that more than 30 million men and women will suffer from a clinically significant eating disorder at some point in their life. The research is clear that the earlier these behaviors and symptoms are identified and effectively treated, the greater the chance for a full recovery. While there is a strong biological component, there are absolutely steps parents can take to create a healthy environment, promoting and maintaining for their children a normalized and balanced relationship with food, exercise, and their bodies.

Here are some ways that you can help your child develop a healthy relationship with food and their body to prevent against disordered eating:

- Set a good example of healthy eating. Teach your child to enjoy ALL foods. Stay away from labeling foods as “good” or “bad.” Don’t allow your child to diet, unless under the direction of a medical doctor. Ninety-eight percent of eating disorders develop after starting a diet.

- Be a good role model. Your child watches your relationship with food and your body. Be sure that you are sending them the messages that you want them to hear.

- Encourage your child to be active. Find a sport or activity that your child enjoys. Kids should focus on playing – not on spending time in the gym. Be active with them. Go outside and play with your child or go on a family walk.

- Value your entire child. Make sure you compliment your child on who they are — their gifts, their personality, their lovable traits. Help them to understand that who they are is more important than their appearance.

- Teach your child how to be media-literate. Help your child to understand the messages the media may send us about how we should look, and that images are often altered to fit a certain type.

- Be aware of warning signs. These can include changes in eating patterns, changes in mood, preoccupation with food or their bodies and withdrawal from normal activities.

If you believe that your child is struggling, contact a professional. While disordered eating is on the rise in children, effective treatment is available.

At Southeast Psych, Juliet Lam Kuehnle MS, NCC, LPC, specializes in treating boys and girls ages eight and up with eating issues, grief and loss and mood disorders. She is trained in EMDRtherapy to use with trauma and other negative areas where clients are stuck.

Dr. Heidi Limbrunner is a board-certified clinical psychologist at Southeast Psych specializing in the treatment of disordered eating and body image. She has spoken nationally and internationally on the topic of eating disorders in adolescents.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Parents’ Post-Delivery Worry: An Incomplete Esophagus

The amazing and usually seamless process of a child forming in the womb — it’s nothing short of a miracle! Two cells join and divide billions of times into different tissues to create a living, breathing human being with everything in the right place. But occasionally something does happen in this incredible chain of events, leading to the improper formation of an organ. And sometimes that organ can be the esophagus, the tube that carries nourishment from the baby’s mouth to his or her stomach.

The amazing and usually seamless process of a child forming in the womb — it’s nothing short of a miracle! Two cells join and divide billions of times into different tissues to create a living, breathing human being with everything in the right place. But occasionally something does happen in this incredible chain of events, leading to the improper formation of an organ. And sometimes that organ can be the esophagus, the tube that carries nourishment from the baby’s mouth to his or her stomach.

This sounds terrifying, and indeed, it is a harrowing experience for parents struggling to understand why their baby cannot eat, breathe or stop vomiting during feeding. Esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula (or EA with TEF) occurs in about 1 out of every 5,000 births. Fortunately, this is something pediatric surgeons are trained to help correct and the rate of success is very high.

Here’s more about the condition and what it looks like inside the baby’s body:

The esophagus is a muscular tube that squeezes food and drink from the throat down to the stomach. It is positioned in the chest directly behind the trachea (or windpipe), which carries air to and from the lungs. Occasionally the esophagus, rather than being a single continuous tube, does not form properly and ends up being two separate segments. One segment connects to the throat and one to the stomach, but they do not connect to each other. This is known as esophageal atresia. In this condition, the infant is not able to eat since food cannot reach the stomach through this tube. Frequently, when this occurs, there is also an abnormal connection of one or even both segments of the esophagus to the nearby trachea. This abnormal connection is called a tracheoesophageal fistula. In this case, not only can the newborn not feed, but the connection (most frequently between the trachea and the lower segment of the esophagus connecting to the stomach) allows gastric fluids to reflux directly into the lungs. This can injure the newborn’s delicate lung tissue.

It is almost impossible to diagnose EA with TEF prenatally, and is usually discovered very soon after birth with symptoms of difficulty breathing, choking or vomiting during any attempt at feeding. When suspected, the malformation is diagnosed with an x-ray.

Once diagnosed, the patients are transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and an urgent consult is made to a pediatric surgeon. Ultimately, the infant will have to have surgery to correct the abnormal esophagus. Should this ever happen to you or a loved one, the surgeon will guide and advise you through those decisions based upon what he or she sees during the physical exam and in reviewing the imaging studies. Not all EA with TEF patients are the same and the treatment plan can vary significantly.

It’s important to note that there are varying degrees of severity in EA with TEF, and many children do very well long-term. Occasionally some children will have problems with heartburn as they grow and develop. The esophagus, once connected, can sometimes still not function well, as muscles may have problems, or internal scarring may need to be corrected with additional surgery.

Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula can be very scary, but with the right surgical team, you and your baby can have a very positive outcome.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

By Jessica Bell, MD, and Julia Oesterle, MSW, LCSW, St. Jude Affiliate Clinic at Novant Health Hemby Children’s Hospital

By Jessica Bell, MD, and Julia Oesterle, MSW, LCSW, St. Jude Affiliate Clinic at Novant Health Hemby Children’s Hospital

Pediatric cancer can deprive children of their health, innocence and joy in childhood, and leave parents and siblings struggling to maintain normalcy. Parents who are trying to help their children cope need support themselves, but they may be hesitant to reach out.

People often ask how to best care for a family facing the complexities of childhood cancer. Expressing your support can help carry families through difficult times and even small gestures of love can make a powerful difference.

While we cannot know what every family wants or needs, there are many ways to offer kindness and assistance. Here are some suggestions to help you get started:

Reach out

Call, text or write. Don’t be afraid to express your care and concern. Let your connection to the family guide your communication, and be sensitive to their responses.

Parents might struggle with despair, anger or other strong emotions. They may be exhausted after long days of treatment or sleepless nights in the hospital. Even when parents can’t communicate frequently, your support can still provide strength and reassurance. Take advantage of communication trees or shared websites to help you stay connected.

Give Your Time

It would be remiss to not address the traditional comfort of food. Prepare meals that freeze or keep well and set up a shared meal schedule with others who want to help. It’s helpful to ask the family about food preferences since chemotherapy can affect a child’s sense of taste or smell.

Gift cards can be helpful since they give the family choices and flexibility. Also consider acts of service for specific family members. Siblings might need help with carpools or after-school activities, and parents might need help with errands.

Coworker support can be invaluable to working parents who depend on their employment. Encourage parents to explore more flexible hours, the ability to work off-site or take advantage of others’ contributions toward additional time off.

Be Flexible

Cancer treatment can be unpredictable in how it disrupts a family. Everyone is affected by unexpected or prolonged hospital stays. Helping with household tasks, including picking up mail or packages, taking care of pets or mowing the lawn, allows parents to focus on their child.

Since many people are used to relying on their own strength and independence, it can be difficult to accept help. Offer, rather than ask, making a specific offer like, “I know you’ve had to stay in the hospital with your child, so I’d like to mow your lawn” instead of, “Let me know if you need anything.” Being specific and intentional can alleviate others’ discomfort in accepting help.

Be Mindful

Patients may have certain medical restrictions, but they can still pursue many of their normal activities. Engage with the family while respecting their needs and preferences. Children receiving chemotherapy have a higher risk for infection, so check with the family before visiting. Patients also have a variety of symptoms, including fatigue, nausea or easy bruising. When planning an event, be flexible with the time and type of activity so that the child can have fun when feeling up to it.

Love Without Conditions

As you surround a family with love and support, you may not get any feedback. A family focusing all of its energy fighting cancer may not have much left for day-to-day interaction. Since most people aren’t experts in communicating during tough times or understanding medical crises, give yourself permission to make “mistakes” in your offers of care.

Most importantly, remember that when you genuinely express your concern and love for a child battling cancer, you will certainly make a meaningful impact on the child and the entire family.

While some people shy away from hematology and oncology, Dr. Jessica Bell feels called to the field. She supports children and their families on their cancer journeys. Dr. Bell has been a part of the St. Jude Affiliate Clinic at Novant Health Hemby Children’s Hospital since 2008.

Julia Oesterle has long been a clinical social worker serving children and families and joined the St. Jude Affiliate Clinic in 2017. As a counselor and parent, she feels most privileged to work with patients and parents of the St. Jude Affiliate Clinic as they move through their unique health-related challenges.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.

Childhood Cancer and Everyday Heroes

By Jessica Bell, MD

St. Jude Affiliate Clinic at Novant Health Hemby Children’s Hospital

Most days, we find ourselves moving through our familiar routines. We get our kids to school, present a proposal at a meeting, meet some friends at the gym, grab groceries, put a meal on the dinner table, and run a load of laundry for the shirt that must be worn to school the next day. We try to do our best, and we make choices that can seem ordinary but are quietly heroic.

Most days, we find ourselves moving through our familiar routines. We get our kids to school, present a proposal at a meeting, meet some friends at the gym, grab groceries, put a meal on the dinner table, and run a load of laundry for the shirt that must be worn to school the next day. We try to do our best, and we make choices that can seem ordinary but are quietly heroic.

It can be difficult to imagine that in addition to these efforts, some parents must add yet another heroic action to their day—taking their child to a chemotherapy appointment.

The parents who come into the St. Jude Affiliate Clinic are the heroes who live in your neighborhood, pass you in the carpool, shop at your store, or sit at the table next to yours at your favorite restaurant. When I see them in the office, these parents may be wearing business suits, sweatpants, high heels or sneakers. The commonality among them? None ever expected their entire world to be torn apart because their child developed cancer.

The C Word

The C word . . . we fear it. Even if it has not affected us personally, we are aware of its presence in our lives and can’t believe that such an ugly thing exists.

Pediatric cancer affects families of all incomes, ethnicities and beliefs. Almost 16,000 children this year will be diagnosed with cancer in our country. In the modern era, pediatric cancer has more than an 80 percent chance of being cured. That cure rate is both hopeful and alarming at the same time, because a fight against childhood cancer is an all or nothing battle. There is no second place, and survival rates can vary greatly based upon such factors as the child’s age, the type of cancer or the stage of the cancer.

Although cancer is horrific, we must remember that pediatric cancer cure rates continue to rise because clinical research has steadily provided better treatment options. Even some of the most devastating diseases, such as Stage 4 neuroblastoma, are now treatable because of the efforts of oncologists, researchers, parents and patients.

Cancer treatments may now include combinations of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, immunotherapy and drugs that target small molecules. Researchers are also working to understand the genetic code of a patient’s cancer so that we can safely overcome even the most resistant cancer cell, while simultaneously decreasing the severity of side effects. These breakthroughs are possible through collaborative efforts of medical teams and researchers all across the world, because we share the common goal of finding a cure for every child with cancer.

Increasing awareness of pediatric cancer allows our community to support vital research and provide timely access to medical care. Recognizing that pediatric cancer can affect anyone also encourages us to reach out to those families who are deep in treatment, to lift them up and help them persevere.

Rather than cover our eyes and hope the dreaded “C word” will somehow pass by us, we must be as brave as the children and their parents who confront cancer on a daily basis.

Talking About Childhood Cancer

You may find that pediatric cancer becomes a topic of discussion because of a schoolmate, a neighbor or a relative. There is no single right way to talk about cancer, so the first step is being willing to have a dialogue. If you accept that there will be awkward moments in the conversation, then those moments are easier to navigate. Even acknowledging your embarrassment can put the other person at ease. Once your family and friends realize that they have a safe space in which to talk, these difficult conversations can be incredibly rewarding.

When talking to a child, breaking down scary terms into more familiar concepts can help a child cope with what they are inevitably hearing. The words you use depend greatly on the individual’s developmental stage and past experiences. Sometimes we have to disassociate from our preconceptions of medical terms like cancer, tumor, mass, benign and malignant, and use the words to best explain the situation.

When talking to the elementary school child, I may describe cancer cells as a new lump inside the body that is not normal and shouldn’t be there, like a weed in a garden. Those cancer cells have become mean or stupid, and they don’t know they are supposed to stop growing, so the doctors may have to use surgery or medicines (pulling the weeds or spraying with weed killer) to get rid of the cancer cells before they cause more problems.

For an older child who has become versed in technology, I may explain that the program or code of the cells is no longer working properly and the cell has become programmed to grow out of control. Even for adults, it is sometimes important to remind ourselves that the cancer is not contagious, the child did not “do” anything to become at risk, and there are treatment options to offer hope for a cure.

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to talking about cancer. It’s important to note that kids can come up with great questions. My best advice is to ultimately be honest in your answers, even if that means saying, “I don’t know.” Many answers are still out of reach for any of us. Honesty also means that we should only make promises that we can keep. We can’t always promise that everything will be all right, but we can promise our everlasting love for our children that will endure far beyond a diagnosis of cancer.

Don’t let cancer hide itself because we don’t want it to exist. As just one of many health issues we have to face, it’s OK to talk about cancer so that we can ultimately defeat it.

While some people shy away from hematology and oncology, Dr. Jessica Bell feels called to the field. She supports children and their families on their cancer journeys. Dr. Bell has been a part of St. Jude Affiliate Clinic at Novant Health Hemby Children’s Hospital since 2008.

This blog was produced in partnership with Charlotte Parent. Click here for the original post and other parenting resources.